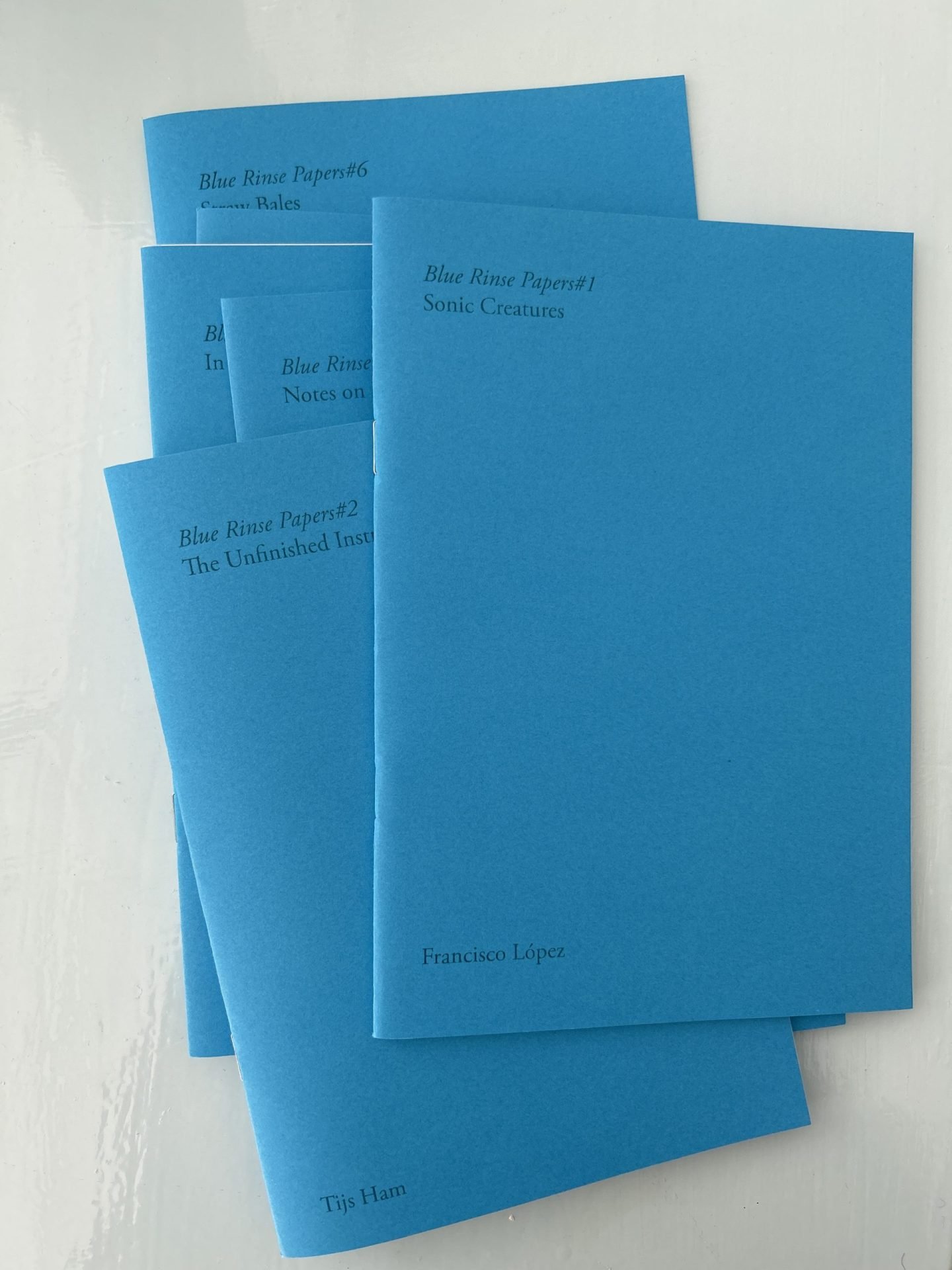

Blue Rinse Papers

The Unfinished Instrument

The Unfinished Instrument

Pliancy and Processes of Perpetual Discovery

A few decades ago, as I roamed around the family house as a kid, hunting for a fresh toy to play with, I

spotted this old acoustic guitar. Although it had already been part of the household before I was born, it

must have taken about eight or nine years before it attracted my attention. The guitar was a 1960s

model classical guitar, significantly smaller than most contemporary designs, which perhaps only

contributed to my young curiosity. My father, a retired music teacher at that time, was not a particularly

proficient guitarist. Still, he knew more than enough about the basics to be able to tune the neglected

instrument and teach me where to place my fingers and how to strum the strings. As I tried to copy his

movements, I soon managed to replicate some of the chords and turn them into naive songs. More

importantly, as this journey continued, I slowly began to grasp the relationships between the tension of

the string, its length, and the resonances it produced. Before long, new chords and, eventually, tuning

systems emerged through playful experimentation. Each time I fiddled with the tuning pegs, it enriched

the space of sonic possibilities. The guitar could always be changed and, through that change, be

discovered anew.

Unfinishedness

Although the guitar mentioned in this anecdote above would generally be considered a ‘finished’ instrument,

one could argue that it holds the potential to be subjected to adjustments or reconfigurations. What, then, does

it mean for an instrument to be finished? It may be tempting to suggest that as a luthier hands his work over to

an instrumentalist, the instrument itself is finished. Yet, in his book ‘The Order of Time,’ the theoretical physicist

Carlo Rovelli[1] points to the following suggestion, revealing that things might be more nuanced than initially

stated.

“The entire evolution of science would suggest that the best grammar for thinking about the world is that of

change, not of permanence. Not of being, but of becoming”

C. Rovelli (2018, 86)

Forces of Change

From this observation, we may conclude that however robust and finalized any instrument may appear, it is

nevertheless part of this world and thus affected by the forces of change that govern it. Heat, frost, humidity, and

usage have continuous effects on its surface, materials, and operation. Left to its own devices and given enough

time, any instrument will slowly deteriorate until it turns or rather returns to dust. Counteracting these

processes of change, luthiers provide means to adjust their instruments to the environments to which they are

exposed. The tuning pegs of the guitar address the detuning effects of the expansion and contraction of the

wood on the strings. In turn, these very same measures can be utilized to make decisively musical alterations to

the instrument’s character, opting for alternative tunings, exploring microtonality, or changing the strings

altogether for a change in timbre. That which increases permanence simultaneously increases its potential for

change.

Temporary Passages of Finality

Perhaps we can explore a different perspective on finishing or finality. Although the nature of time points to a

worldview based on everlasting change, it is possible to imagine specific passages along these plains of change

having a varying sense of finality attributed to them.

Let us compare a solo jam session in the comfort of one’s studio to a world premiere as part of a

prestigious festival for a distinct audience. In both of these circumstances, performances take place, yet,

in each case, there are different kinds of consequences attached to the activity. The combination of the

fleeting temperament of the present and audience expectations establishes a level of urgency, leaving a

mark on that particular time and space in memory. Through this mark, the moment of performance

carries its sense of finality. Where the studio jam is practically consequence-free, a world premiere will

channel the sense that days, weeks, months, and perhaps years of preparation have led up to this singular

point of consequence.

Time itself does not stop in its tracks, and these consequential events pass through their nownesses to be added

to an ever-increasing past. Yet, to take any temporal art form seriously, it is required to attribute urgency to its

moment of becoming, and through this urgency, a temporary passage of finality is established. As the performer

enters the stage, the affordances and ergodynamics[2] of the instruments are there for all to witness. This is

perhaps why many performers prefer to play instruments that express a sense of permanence. This is also why

most tend to tune their instruments before a concert starts, avoiding the uncomfortable surprise of unexpected

pitches amid a performance. So, while it seems logical to opt for an instrument that responds in certain and

reliable ways, the unfinished instrument investigates an alternative path, embracing the discoveries and surprises

that arise when playing an instrument that remains open to the processes of change.

Intentional Instability

There are many approaches to the designing, building, and playing of instruments, each tackling the knowns

and unknowns related to the changing nature of instruments in their own ways. With the evolution of

mechanical, electronic, and digital instruments, new possibilities have begun to surface, enabling further

negotiations between reliability and possibilities for sonic surprises by implementing non-linear, recursive, or

stochastic principles. In effect, these negotiations reveal the intricate connections between the design of

instruments and the experiences of the instrumentalist and how each informs the other.

Pliancy

It is at this point that it becomes useful to look at instruments as pliable entities, able to adapt to changing

circumstances and express flexible qualities. This pliancy of instruments can be divided up into three somewhat

overlapping categories.

First, there are the handles that allow performers to adjust the instrument’s operation to their liking. Examples

of these could be the tuning pegs as mentioned above, or the mutes used to alter a trumpet’s sound. In both of

these examples, the instrument can undergo changes either to ensure reliability, keeping the instrument in tune,

or making alterations that spark exploration. As a rule of thumb, handles are often set before actual

performances, but of course, there are many exceptions to this, which leads us to the second category.

These are the sonic responses of the instrument through play. Here, we can distinguish between intended use,

applying the techniques that the instrument has been optimized for, and playing techniques that explore the

instrument’s complete potential as a resonator. Depending on the experience and skill set of a performer, many

of these techniques can be reproduced with remarkable accuracy, but if one pushes the boundaries even further,

we will reach our last category.

Now, we arrive at the underlying instabilities of the instrument itself. Here, we can assess situations in which the

instrument behaves on its own accord, regardless of the use to which it is subjected. A simple example would be

the snapping of a string. Still, perhaps there are more alluring qualities to be found in the turbulences and other

non-linearities that are unleashed at the outer edges of an instrument's sonic capacities. One could say that it is

here that the instrument begins to correspond[3] to the performer on its own terms, something that is mirrored in

the language that is used by those who explore these artistic regions. The artist Toshimaru Nakamura,[4] for

example, describes an attitude of obedience and resignation as he plays with his chaotic instrument, the No-Input

Mixing Board.

It is within this last category that the unfinished instrument emerges. Instruments centered around their

turbulences and non-linearities, intended to be played as an act of exploration, with handles to dial in on its

tipping points unto the unforeseen. Instruments that showcase sonic behaviors through animated gestures;

instilling a sense that the instrument has a voice of its own.

Shades of Influence

Once the instruments we perform with are no longer defined by their reliable responses, we eventually reach a

point where it is no longer useful to think about performance as an act of control over an instrument. Instead of

playing on the instrument, we start to play with the instrument alongside it. In these situations, it makes sense to

think of performance as taking part within a sphere of influence on the sonic expressions that come about in a

collaborative setting between performer and instrument. The instrument is to be approached with curious

attention, engaging in correspondences of performative gestures and sonic behaviors, each influencing the other.

Composer and performer David Dunn[5] brings forth the following analogy as he describes his relationship with

one of his chaotic instruments in the book ‘Haunted Weather’ by David Toop. [6]

“While I can influence the complex behaviors, I cannot control them beyond a certain level of mere

perturbation, the amount of which is constantly changing. The experience is often tantamount to surfing

the edge of a tide of sound that has its own intrinsic momentum.” (Dunn, Toop, 2004, 193)

Notice the aquatic character in the metaphor of the tide that Dunn puts forward and, along with it, associations

of fluidity, ranging from gentle ripples to fierce turbulent flows. If we would argue that playing with the

unfinished instrument is reminiscent of exploration, then the site of that exploration would have to be described

as being liquidic in nature. Drifting from and returning to a specific ‘location’ will always bring about a change

to that location itself, possibly rendering it unrecognizable in the process. This environment is never quite

stationary, but instead, governed by currents, tides, and waves, embodies a sense of movement prior to any

deliberate maneuver through it. Indeed, negotiating a path through the tide requires an acute awareness of what

these waters bring to bear and where these waves may take you.

There are many different shades of influence that characterize the playful interactions between performers and

instruments. These unfold, on the one hand, in the skills, curiosities, and experiences of the performer and the

various forms of instrumental pliancy on the other. Whereas some instruments are optimized to deliver reliable

sonic responses and allow for the development of virtuosic performance skills through dedicated training and

rehearsals, other instruments may defy any form of performative influence. However, neither of these extremities

turns out to be realistic in practice. However optimized, instruments always maintain some surprising elements,

and likewise, even the most chaotic instruments can still be influenced, at least to some small extent.

The unfinished instruments could be thought of as occupying the middle section of this spectrum, uid and

pliable enough always to evade full control but still responsive enough to be influenced through playful

explorations, enhancing the skills required to encounter the unknown. The writer Rebecca Solnit[7] reflects on

this topic in her book ‘A Field Guide to Getting Lost’ in the following manner.

“For it is not, after all, really a question about whether you can know the unknown, arrive in it, but how to

go about looking for it, how to travel”

(Solnit, 2005, 24)

Perpetual Discovery

I’m seated behind my desk at my studio, the double doors closed shut, locking me into an acoustically

isolated environment. In front of me is a selection of guitar pedals, some of which I have designed in

collaboration with Pladask Elektronik.[8] The pedals are linked up through a matrix mixer, routing the

electronic signals through interconnected feedback loops. There is no guitar attached to these pedals,

yet they sing, whistle, growl, and sputter of their own accord. I squinted my eyes to focus my attention

on the waves of sounds emitted from the speakers. Some minutes ago, my hands were still on the dials

and knobs, influencing patterns and intensities, but for some time now, I’ve just been listening. A

focused, concentrated form of listening. An evocative act of curiosity, taking in the tidal rhythms and

melodies and contemplating what exactly it is that I experience. What are these sonic behaviors

expressing? Who or what is speaking? And conversely, where do I find myself within this conversation?

Perhaps the unfinished instruments could be better described as being open-ended instruments. Always ready to

provide variation and difference, perpetually bifurcating unto new paths, suggesting one to wade through the

unfamiliar waters. For it is precisely in this middle of the unknown that expectations are breached and, with any

luck, exceeded. With time and practice, and through engaged listening and careful navigation, one can learn to

anticipate and recognize the surprises that are encountered.

“To describe any material is to pose a riddle, whose answer can be discovered only through observation and

engagement of what is there. The riddle gives the material a voice and allows it to tell its own story; it is up

to us, then, to listen, and from the clues it offers, to discover what is speaking.”

(Ingold 2013, 31)

It may very well be fruitless to differentiate between these open-ended, unfinished instruments and all those

other instruments that do not subscribe to that description. Through experimentation and curiosity, any

instrument can become a springboard for an exploration of unforeseen qualities, uncovering the instabilities that

have been hiding in the corners all along. The unfinished instruments are the instruments of change and

becoming.

Notes

1. Carlo Rovelli is an Italian theoretical physicist and writer. His work is mainly in the field of quantum gravity, where he is among the founders of the loop quantum gravity theory.

2. Thor Magnussen is a professor of Future Music at the Music Department of the University of Sussex. In his book ‘Sonic Writing,’ Thor Magnussen describes the concept of ergodynamics as follows: “The concept signifies the instrument’s potential for expression, what lies in it, its discoverability, mystery and magic.” (Magnussen 2019, 10)

3. Tim Ingold is a professor in the department of Anthropology at the University of Aberdeen. He writes about the concept of ‘correspondence’ in his book ‘Making,’ framing it as the back and forth between the maker and the materials that are employed in the course of making, each informing the other how to proceed.

4. Toshimaru Nakamura's instrument is the no-input mixing board, which describes a way of using a standard mixing board as an electronic music instrument, producing sound without any external audio input. [...] The unpredictability of the instrument requires an attitude of obedience and resignation to the system, and the sounds it produces, bringing a high level of indeterminacy and surprise to the music. http://www.toshimarunakamura.com/bio - accessed on 04 - 11 - 2020

5. The composer David Dunn, a student of Harry Partch, has devoted his musical career to assembling "Environmental sound works,” which somehow represent the environment and its biological essence.

6. David Toop has been developing a practice that crosses boundaries of sound, listening, music, and materials since 1970. This encompasses improvised music performance, writing, electronic sound, eld recording, exhibition curating, sound art installations, and opera.

7. Writer, historian, and activist Rebecca Solnit is the author of twenty books on feminism, western and Indigenous history, popular power, social change, insurrection, wandering and walking, hope and disaster, and most recently, The Mother Of All Questions. http://rebeccasolnit.net/

8. Knut Olai Mjøs Helle is the founder of Pladask Elektronisk, a small effect pedal manufacturer based in Bergen, Norway, with a focus on experimentation to create unique and interesting effects. https://pladaskelektrisk.com/about/

References

Rovelli, Carlo. The Order of Time. Penguin Books, 2019.

Toop, David. Haunted Weather: Music, Silence, and Memory. London: Serpent’s Tail, 2005.

Solnit, Rebecca. A Field Guide to Getting Lost. USA: Canongate, 2017

Ingold, Tim. Making. New York: Routledge, 2013.